In October and November 2018 we conducted a survey to assess privacy concerns in smart cities across Canada. It asked: what are the expectations of Canadians with regards to their ability to control, use, or opt-out of data collection in smart city context? What rights and privileges do Canadians feel are appropriate with regard to data self-determination, and what types of data are considered more sensitive than others?

Read our full 13-page report here.

Read our published findings: Bannerman, Sara, and Angela Orasch. “Privacy and smart cities.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 29, no. 1 (2020): 17-38. Available at: https://cjur.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/cjur/article/view/268 (Open Access).

Survey findings

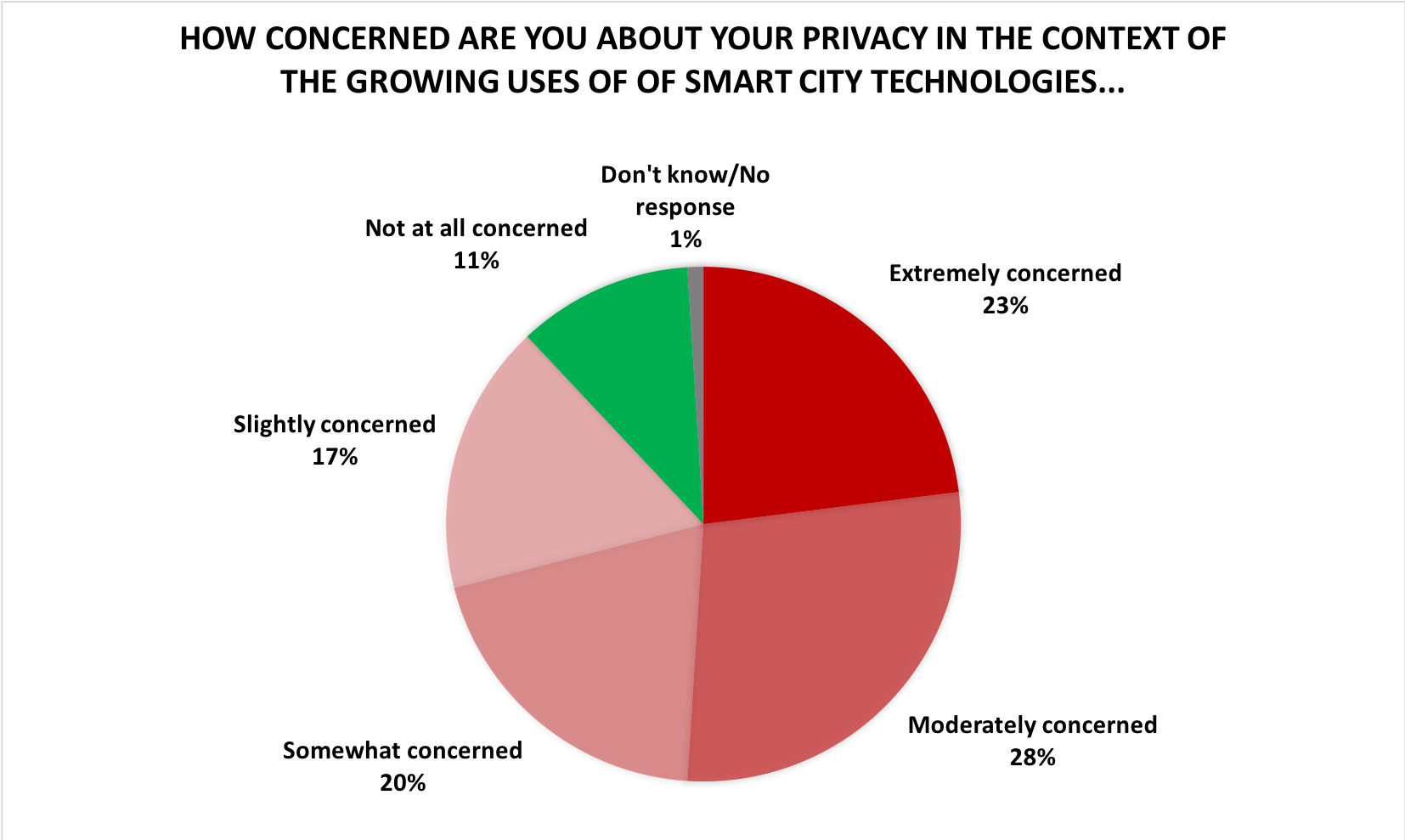

The preliminary question of the survey asked, “How concerned are you about your privacy in the context of the growing uses of smart city technologies?”. The survey found that 88 percent of Canadians are concerned on some level about their privacy in the smart city context, with 23 percent being extremely concerned, 29 percent moderately concerned, and 19 percent somewhat concerned.

Angela Orasch, one of the lead researchers in the survey project, said:

The growing use of ‘smart’ technology in Canadian cities has elevated concerns regarding the collection, storage and usage of personal data. The high-profile case of Sidewalk Labs’ Quayside project in Toronto has brought this issue into the mainstream. Transportation technologies which track one’s location, noise monitoring systems that can record passers by, crime analytics that can be used to zero-in on specific neighbourhoods, and ‘smart’ benches that connect your hand-held devices to ports – all of these technologies raise privacy concerns.

Sara Bannerman, Canada Research Chair in Communication Policy and Governance at McMaster University and one of the lead researchers in the project, said that the survey shows that Canadians have a high level of concern about smart city privacy. “All levels of government must put in place strong privacy protections, including a smart city privacy policy co-developed with privacy regulators,” she said.

When asked about private uses of their personal information, such as use of personal information to plan and refine private businesses or to target ads, or the sale of their information, on average 72 percent of Canadians said that such for-profit uses of their personal information “should not be permitted.” A further 24 percent of Canadians said that such uses “should be permitted, but only if I am granted certain rights and protections for my data.”

Canadians most object to the sale of their personal information and to the use of their personal information to target them with ads. Ninety-one percent of Canadians said that the sale of their personal information should not be permitted. Sixty-nine percent of Canadians said that the use of their personal information to target them with ads should not be permitted.

Canadians most object to the sale of their personal information and to the use of their personal information to target them with ads. Ninety-one percent of Canadians said that the sale of their personal information should not be permitted. Sixty-nine percent of Canadians said that the use of their personal information to target them with ads should not be permitted.

When asked about whether they would permit the use of their personal information for public uses such as crime prevention or traffic and city planning, 50 percent of Canadians said such uses “should be permitted, but only if I am granted certain rights and protections for my data,” while 29 percent said such uses “should not be permitted.”

The survey asked Canadians about whether certain uses of personal information that are often associated with smart cities should be permitted. It showed that people are far less willing to permit for-profit uses of their personal information, compared with municipal government uses. Bannerman noted:

The majority of Canadians do not think that for-profit uses of personal information should be permitted at all. Between 55 and 91 percent of Canadians said that for-profit uses “should not be permitted” depending on the specific use. Canadians are more open to government uses of information such as in traffic and city planning, especially if they are granted rights and protections in their data. This should cause municipalities to think twice about instituting smart city projects that are profit-motivated or business-led.

Bannerman noted:

Few Canadians think that the use of their personal information should be permitted by default. Canadians want control of their data that goes beyond simple notice of how their data is used somewhere in the fine print. They want the options to opt out; opt in; view, delete, correct, and download their data.

The survey indicated that men are generally more permissive than women about the sale or use of their personal information for ad targeting or in traffic and city planning.

Women are more likely to object to the sale of their personal information or its use to target them with ads. However, they are more willing than men to have their personal information used in crime prevention, as long as they are granted certain rights and protections for their data.

Participants who were visible minorities and Indigenous or aboriginal people were more likely to say that the use of their personal information by police in crime prevention should not be permitted.

Participants under 35 were more open to allowing their personal information to be sold or used for ad targeting, behavioral modification, or traffic and city planning, if given control of that information, such as the ability to opt in, opt out, download, or delete their data. “I think, and our survey demonstrates this, younger participants are less likely to agree that they should put up with service providers’ privacy policies, that not using a service is a viable alternative to “take-it-or-leave-it” privacy policies, said Bannerman.”

Middle-aged participants (age 35 to 44) are more likely to say that that the use of their personal information to plan and refine private businesses to make them more profitable, or in crime prevention, should not be permitted. Those age 65 and up are more likely to object entirely to the sale of their personal information, or its use to target them with ads or in efforts to modify behavior. At the same time, those age 65 and up are more permissive about public uses of their data by police in crime prevention, or in traffic and city planning.

According to the survey, which was conducted in October 23 to November 1 2018, twenty-three percent of Canadians are extremely concerned about their privacy in the context of the growing uses of smart city technologies, 28 percent moderately concerned, 20 percent somewhat concerned, and 17 percent slightly concerned about their privacy in the context of smart city technologies. Just eleven percent of Canadians are “not at all” concerned.

This survey was funded by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC). The views expressed herein are those of the project researchers and do not necessarily reflect those of the OPC.

The margin of error for this survey is +/-3.08, 19 times out of 20.

The survey results are available here, in table format.

The raw data is available here.